Andrew Bullard

To be, or not to be, that is the question—

Whether ’tis Nobler in the mind to suffer

The Slings and Arrows of outrageous Fortune,

Or to take Arms against a Sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them?

-William Shakespeare, Hamlet

In what is perhaps one of the most well-known soliloquies written by William Shakespeare, Hamlet has reached a crossroads. Is it better to be complacent and deal with the problems life presents or should one take up arms in an attempt to fix them? It would seem that humanity has reached a similar junction. What actions, if any, should we take in regards to the Anthropocene? This is a tough question and requires some breaking down. We are really facing two different questions here: should we do anything and what exactly should we do.

The first part is probably the easiest to answer. Humanity has been impacting the environment for millennia. We have been altering and manipulating the Earth to fit our needs, and have now become a driving force in many of the Earth’s natural processes. In fact, a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene, has been proposed based on human activities. The major concerns plaguing this so called “age of man” include climate change and loss of biodiversity. However, as many scholars and scientists have pointed out, these are not new concepts. Global temperatures have fluctuated in the past and, to date, there have been 5 mass extinctions. So we should have nothing to worry about as all of these environmental transformations are completely natural. Still, the fact remains that none of these past events have been caused by life itself, that is to say there have been extenuating circumstances (i.e. giant asteroid, or volcano eruption). There is also the issue of rates. We have been emitting more and more carbon into the atmosphere, so much so that we are overwhelming the Earth’s natural carbon removal systems. Additionally, if current extinction rates continue, we could see a sixth mass extinction within the next 500 years. I hate to focus on the doom and gloom, but that is the situation we currently find ourselves in. We also need to come to terms with the fact that the majority of these extreme changes are humanities fault. We made this mess, so we are morally and ethically responsible for fixing it. This brings us to the second part of our question: what is the best way to go about reversing the impending doom.

There’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

This second part is the one that plagues many governments and citizens alike. As Hamlet says so eloquently, there is a reason our problems have gotten out of hand: we are not exactly sure what we should be doing to fix them. However, that is not to say that we are doing nothing. In fact, there has been significant progress in regards to finding a solution to the Anthropocene problem. One such answer, which I will discuss here, is the process of carbon offsetting. Carbon offsetting involves the purchase of ‘credits’ from companies or groups that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and overall carbon waste production. By buying these credits, businesses or even individuals can help compensate for their own carbon production, which, as Diana Liverman points out in her paper “Carbon Offsets, the OCM, and Sustainable Development,” can be extremely useful in countries lacking the ability or drive to reduce carbon emissions domestically. The creation of the offsetting process has its roots in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. Though the treaty was not really effective overall, it helped set a precedent for future, more binding, international commitments. Still, the treaty signed in Kyoto helped legitimize the idea that offsetting carbon emissions could be an effective way of dealing with the new epoch. Carbon offsetting, in general, makes a lot of sense. Since the Earth’s atmosphere is mixed equally, carbon reduction processes can happen anywhere. For example, the emissions produced in the United States could be offset in countries in Africa or Indonesia. In these places in particular, land and labor are usually cheaper, making the buying of credits more attractive to businesses. The offsets also help these ‘third-world’ countries by providing another sources of jobs and income in addition to helping these developing nations enter the conversation about climate change. Emission reduction projects also help to educate people in developed countries to be more mindful about their own carbon production.

However, it is a fact of life that with good comes bad and carbon offsetting is not without its share of troubles. One concern with this method of greenhouse gas reduction is the idea that the offsetting process is unethical. “It is unethical to buy your way out of your carbon guilt by purchasing low-cost offsets to compensate for a high consumption-lifestyle (Liverman).” Buying offset credits can reduce the desire to slow carbon emissions and seems to lessen the weight of responsibility on the parties involved. There is also the question of the effectiveness of offsets in helping to permanently reduce emissions. Some offset projects have failed in the past and many times the cost of these projects are extremely high, especially when it comes to ones involved with the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) under the Kyoto Protocol. There is also the threat of what Liverman refers to as “double counting” credits (credits that are sold multiple times to different buyers) which does not help the offset process in any way.

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

While there are legitimate concerns regarding carbon offsetting, the reality is that people are choosing to not dwell on the negatives and instead are looking at the possibilities carbon offsetting presents. According to a research paper by Valetin Bellasen and Benoît Leguet, companies as well as individuals are beginning to voluntarily offset their own emissions.

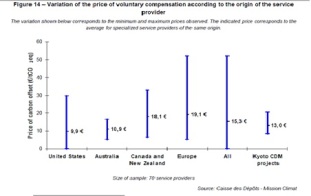

Though businesses and the pubic at large have different reasons for buying voluntary offsets, part of the reason they are so appealing is the diversity of projects. Having more options allows buyers to purchase offsets with projects that they care about (i.e. reforestation, renewable energy, or other anthropogenic issues) as well as projects that are taking place domestically instead of half way around the globe. This helps buyers, and the public in general, become more aware of the offsetting practice as well as letting them ‘do their part’ in terms of fixing the Anthropocene. It also allows them to see what exactly their money is going to. This is of particular importance since when buying offsets, “…customers do not actually purchase a material good for which they have a required need (Lowell et al.).” Additionally, voluntary offsets also have a wider range of prices when compared to those that are provided for by the Kyoto Protocol. A diverse price range opens the possibilities for people to purchase offsets that would not normally be able to do so (i.e. small business owners, low-income households, etc.).

Though businesses and the pubic at large have different reasons for buying voluntary offsets, part of the reason they are so appealing is the diversity of projects. Having more options allows buyers to purchase offsets with projects that they care about (i.e. reforestation, renewable energy, or other anthropogenic issues) as well as projects that are taking place domestically instead of half way around the globe. This helps buyers, and the public in general, become more aware of the offsetting practice as well as letting them ‘do their part’ in terms of fixing the Anthropocene. It also allows them to see what exactly their money is going to. This is of particular importance since when buying offsets, “…customers do not actually purchase a material good for which they have a required need (Lowell et al.).” Additionally, voluntary offsets also have a wider range of prices when compared to those that are provided for by the Kyoto Protocol. A diverse price range opens the possibilities for people to purchase offsets that would not normally be able to do so (i.e. small business owners, low-income households, etc.).

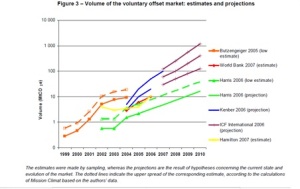

However, as Bellasen and Leguet point out, there are similarities between the carbon offset process and other “ethical approaches” like buying organic and fair-trade. “Like those approaches, it is possible that the voluntary offset market will remain a niche market intended for a few responsible customers.” But this in no way should diminish the effect carbon offsetting can have on climate change. “Its role as a field for learning and pooling emission reduction methods for mandatory carbon markets is recognized by all the [parties].” Even though the current demand for voluntary carbon offsets is small at the moment, it is projected to move away from the niche market scenario and into the main stream.

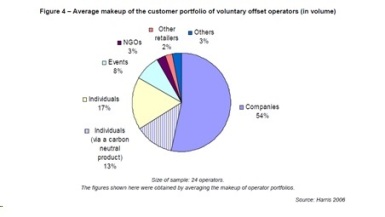

This idea of increasing consumption of offsets is seconded by Heather Lovell and her colleagues (including Diana Liverman) in their paper Carbon Offsetting: Sustaining Cosumption?. In their paper they discuss, at length, the process of marketing offsets to a wider audience and the effect it has had on the offset market. According to their research, the majority of consumers in the offset market are at the corporate level. “Making carbon offset consumption possible is in many ways taking place from the top down as offset organizations, corporations, and the state compete to define and provide ‘ethical’ consumption in relation to climate change.” Companies produce “narratives” about offsetting which give the public a better idea of the offsetting process and as they become more aware, they proceed to purchase more offset credits. The result, according to Lovell, is a complex, uncertain, yet growing market that “…draws into ethical view many of aspects of day-to-day life…and has the potential to shape trajectories of sustainable development and global environmental change.”

I will be the first to admit that carbon offsetting is not the solution to our concerns about climate and the anthropocene. Carbon offsetting is like a using a piece of gum to help plug up a leak in a dam. It is merely a temporary fix and does little to fix the overall issue. In order to truly fix our problems, we need to move away from reactionary methods and become more proactive when it comes to fixing the anthropocene. However, I believe we are taking a step in the right direction. Carbon offsetting is a viable and sustainable form of “fixing” the Anthropocene. While offsetting may not be the final solution, it can help to mitigate the damage we have caused, and continue to do, to the environment. Lovell and her co-authors summarize this quite nicely. “Offsets are an essential part of an effective climate policy precisely because they can be implemented quickly and at a relatively low cost. Given the level of emissions reductions that must be achieved to stabilize the climate, the growing sense of urgency for immediate action, and the societal cost savings that offsets represent, offsets are an indispensable component to real climate change solutions.”

Sources:

Bellassen et al. The emergence of voluntary carbon offsetting. http://www.caissedesdepots.fr/fileadmin/PDF/finance_carbone/etudes_climat/UK/07-09_climate_report_n11_carbon_neutrality.pdf

Liverman, Diana. Carbon Offsets, the CDM, and Sustainable Development. http://environment.arizona.edu/files/env/profiles/liverman/nobelcausebookchapter112.pdf

Oberthur et al. The Kyoto Protocol: International Climate policy for the 21st Century. Springer, 1999.

Lovell et al. Carbon Offsetting: sustaining consumption? http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/students/envs_4100/lovell_2009.pdf